Singapore

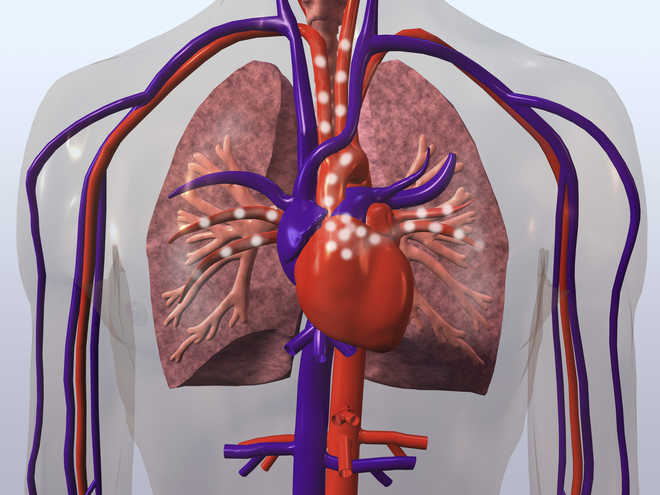

Scientists have developed a new ‘organ-on-chip device’ that mimics atherosclerosis or the constriction of blood vessels, which is the leading cause of heart attacks and strokes.

The device can help better understand heart diseases and test potential drug therapies, without experimenting with lab animals.

In a study published in the journal APL Bioengineering, researchers showed how this organ-on-a-chip could also improve blood testing for patients.

“Atherosclerosis is a very important and complex disease,” said Han Wei Hou, a biomedical engineer at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore.

It develops when fat, cholesterol and other substances in the blood form plaque that accumulates on the inside walls of arteries. This build-up constricts the blood vessel, causing cardiovascular diseases.

Understanding what regulates this abnormal vessel constriction is crucial to studying and treating vessel disease and preventing acute cardiac arrest.

While researchers have previously developed organ-on-a-chip models of blood vessels, those devices focused more on recreating the vessel’s biological complexity than on its shape and geometry – which are key factors in atherosclerosis, Hou said.

“It involves not just the biological aspect of endothelial dysfunction, but also the biomechanics of blood flow,” said Hou.

To address blood flow, researchers built a device that fits on a single square-inch chip, consisting of two stacked chambers separated by a thin and flexible membrane.

The bottom contains air while the top contains a flowing fluid similar in mechanical properties to blood.

Inside the fluid-filled chamber on top of the membrane, the researchers grow endothelial cells—the cells that line the inside of blood vessels.

The researchers pump air into the bottom chamber, so the membrane stretches like a balloon and forms a bubble that blocks the fluid flow. This process simulates the narrowing of a vessel.

The fluid-filled chamber constricts, causing the fluid to flow faster in some regions and slower in others.

When the researchers grew the cells under continuous but slow fluid flow, endothelial cells were able to grow and express a protein called ICAM-1; this protein is associated with inflammation and is important in the development of atherosclerosis.

The researchers found that when they replaced the cell culture media with human blood, more immune cells called monocytes bound to the endothelial cells in low-flow regions.

Monocytes are mainly responsible for the accumulation of lipids, which eventually develop into the plaque that causes atherosclerosis.

These results on a chip are consistent with the widely accepted picture of the disease. Disturbed blood flow in constricted vessels promotes vascular inflammation, which encourages the recruitment of monocytes to help create plaques.

Driving Naari Programme launched in Chandigarh

Driving Naari Programme launched in Chandigarh